- The £150 million Wales JEREMIE Fund that aims to encourage effective investment in small and medium-sized businesses. The Fund is backed by the European Regional Development Fund, the Welsh Government and the European Investment Bank;

- The £40 million Wales SME Investment Fund which is backed by the Welsh Government and Barclays and invests in micro, small and medium-sized firms;

- The £6 million Welsh Government-backed Wales Micro-business Loan Fund;

- The £10 million Wales Property Development Fund, which makes loans to small and medium-sized Welsh construction companies developing small-scale, non-speculative commercial and residential property.

One of the key themes that emerged was that of the cost of debt lending, which a number of respondents had suggested was often higher than the rate offered by the banking sector in Wales. For example, a number of the Welsh Government’s sector panels had concerns about the effectiveness of Finance Wales, stating that interest rates on offer are too high for the market and the security required against loans can be too onerous for small businesses.

Following the first stage of the review, Finance Wales made a formal response to the Minister in which it was suggested that this conclusion was incorrect. The argument used by Finance Wales was that it had to charge higher rates of interest because it had a higher default rate than the banks. As a result, the Minister requested that an examination of the cost of lending and the approach taken by Finance Wales to supporting SMEs should form part of the second stage of the review. This will also help to inform how the Welsh Government’s role could change in delivering finance to businesses in Wales.

Cost of lending to SMEs

Since it was established, Finance Wales has operated a number of funds, all of which have charged different costs of borrowing to Welsh SMEs.

The difference between the average cost of borrowing across all of the funds and the average EU base rate has actually increased from 0.43 per cent in 2001 to 9.69 per cent in 2013 (table 1).

Table 1. Finance Wales – average interest rate for all loans, 2000-2013.

Figure 1: Indicative median interest rates on new SME variable-rate facilities, 2008-2013

As Figure 2 shows, if the difference between the cost of borrowing on each loan since 2001 (in blue) and the EU base rate at the time (in red) is tracked, the difference between the two begins to increase considerably in 2008.

Figure 2: Cost of borrowing on Finance Wales loans, EU base rates, 2002-2013

As will be discussed later, the rationale which has been adopted by Finance Wales for these higher levels of borrowing costs to SMEs will be discussed later and its veracity will be examined in more detail. This is important historically but in terms of this review, the focus will be on the four main loan funds operated by Finance Wales namely Finance Wales III (the interim fund), JEREMIE Fund for Wales, the Wales Micro-business Loan Fund and the SME Fund (Finance Wales suggested that as it manages various funds that range from straight debt through to mezzanine and quasi-equity products, data would be difficult to provide to the review. Therefore, detailed statistics were requested on loans only which make the majority of the borrowings from Finance Wales).

Since October 2007, there have been 743 loan investments made by Finance Wales across these four funds. As Figure 3 shows, 73 per cent of these loans have attracted a cost of borrowing of 10 per cent or higher and there have been only thirteen investments at a rate lower than 8 per cent.

Figure 3. Number of Finance Wales loans by the cost of borrowing, October 2007-

Therefore, the evidence seems to suggest that Finance Wales’ loans are more expensive than the median for UK banking sector, although this must be mitigated by the fact that, according to EC regulations, state-backed funders must offer standard loans at rates that reflect the credit worthiness of the business and the collateral offered against any possible default so that this reflects market rates.

The cost of borrowing and EU reference rates

Finance Wales is an organisation that is wholly owned by the Welsh Government and, given this, there is an expectation that its primary aim must be to support the Welsh economy, particularly the SME sector. One instrument in achieving that would have been through lower interest rates to businesses, especially at a time when banks were not lending for other reasons such as lack of collateral, affordability and overexposure in some sectors.

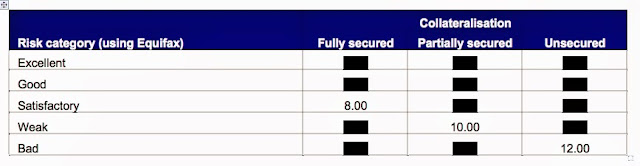

As with all financial instruments supported by European and state funding sources, Finance Wales’ loan funds have to comply with EC regulations on reference and discount rates. Simply put, guidelines have been developed as to the minimum cost of borrowing that can be charged so that it reflects market rates, i.e. is similar to what the private sector would offer and therefore does not breach state aid rules. To determine the actual rate, a new methodology has been drawn up by the EC that takes into account both the credit rating of the business and the collateral it will offer for the loan (table 2).

In this case, the credit rating is obtained from either from a credit agency or a national/government institution) and collateral should be understood as the level of collateral normally required by financial institutions as a guarantee for their loan i.e. the level of collaterals can be measured as the Loss Given Default (LGD), which is the expected loss in percentage of the debtor's exposure taking into account recoverable amounts from collateral and the bankruptcy assets. Therefore, ‘High’ collateralisation implies an LGD below or equal to 30 per cent; ‘Normal’ collateralisation an LGD between 31 per cent and 59 per cent and ‘Low’ collateralisation an LGD above or equal to 60 per cent.

Table 2. European Commission guidelines on loan margins.

Therefore, for an average SME with a satisfactory credit rating and normal collateral that is applying for a loan, the financial institution utilising European or state funding to support its loans programme must, to avoid a breach of state aid rules, charge a minimum of 2.2 per cent above the base rate. Currently, that would be 3.19 per cent (as the base rate is 0.99 per cent). Therefore, the interest rates to be offered can, depending on the creditworthiness and security offered by the business, range from 1.59 per cent to 10.99 per cent.

If EU member states apply the calculation method of these reference and discount rates in force at the moment of the grant of the loan and comply with the conditions set out in that communication, the interest rate does, in principle, not contain state aid. As a result, every publicly backed financial institution, to be compliant with state aid rules, applies the above principles to its debt lending and Finance Wales is no exception.

In a response to the review, Finance Wales stated that their

"State aid legal advice has consistently been based on the view that provided we are lending at a rate that is at least at the EC Reference Rate plus the appropriate risk margin, this is strong evidence that the loans do not contain State Aid. Clearly, the greater the margin over the minimum the stronger such evidence that the loans are at market rates. If we lent money below the minimum margins for the relevant Rating and Collateral indicative margins (most SMEs fall into the BB-CCC or lower categories with low collateral, therefore risk margins are typically 4-10 per cent), this argument of market rates would fall away and a potential state aid challenge become more likely.”

However, the evidence shows that Finance Wales is charging higher margins than that required by the European Commission to satisfy state aid regulations and that there are considerable differences between the cost of borrowing with regard to the reference rates proposed by the European Commission and the different rate categories offered by Finance Wales.

It would have been useful to be able to directly compare the fifteen different rates used by Finance Wales with their equivalent EC rate categories as shown in table 2. However, Finance Wales, despite providing the table below to the review, then withdrew permission to use it within the report. The rationale for this was that the information was commercially sensitive, the pricing guidelines are an internal document and, on their own, do not fully explains how risk is assessed on each investment. This was despite the fact that Finance Wales had already made public their three main categories of risk in the first report; that only thirteen investments in the current fund have been charged at less than eight per cent interest; and that, according to one of their senior executives, Finance Wales is not in competition with other funders as “most applicants to FW have been rejected by the usual sources for funding”.

Table 3. Finance Wales guidelines on loan margins

Nevertheless, the limited comparison of tables 2 and 3, using the published reference rates for three categories, shows that the difference between the EC reference rate proposed and the minimum cost of lending proposed by Finance Wales is as much as six per cent. It has been difficult to determine the scale of this overcharging, as Finance Wales does not keep detailed records of the collateral and credit rating of businesses on its internal IT system and, as a result, it has not been possible in the time available to determine how many businesses may have been paying above the suggested EC rates.

Therefore, the best proxy for this is to examine the individual rates of interest paid by each business according to the three main categories of risk supplied by Finance Wales. This estimates that if the EC reference rates had been adhered to accurately, up to 10 per cent of the current portfolio could have been paying interest rates as low as 1.99 per cent, and a further 50 per cent could have been paying interest rates as low as 4.99 per cent instead of 10 per cent. This would have been achieved without any breach of state aid rules. With regard to the interest rates for companies in bad financial difficulties with low collateral (which would be paying a minimum of 10.99 per cent), the EC recommended rate for Finance Wales is 12 per cent.

This suggests that Finance Wales could have lent at lower interest rates to Welsh SMEs without breaching state aid regulations if it had chosen to do so. In addition, there are also other costs that it charges to Welsh business on top of interest rates as part of the loan process. For example, average monitoring fees are 0.54 per cent, average arrangement fees are 1.8 per cent on current funds. In addition, Finance Wales also charges legal fees.

Table 4: Finance Wales guidelines on interest rates relative to EU guidelines.

The submission from the FSB noted that its members frequently came into contact with Finance Wales, believing it to be an organisation designed to support SMEs with investment but are then disappointed to find very restrictive and expensive lending conditions. One respondent noted: “My surprise to see that the offer on the table is more expensive in interest rates compared to the existing [High street bank] overdraft in place, the personal securities required are the same if not more stringent as from the bank, and on top Finance Wales is asking for 1.5 per cent lending fee, 0.5 per cent monitoring fee and a £275 security fee for the guarantee. This is a more commercial proposal based on stripping from any SME as much money as possible and in direct competition with the commercial banks and not offering small business any benefits at all.”

As with all financial instruments supported by European and state funding sources, Finance Wales’ loan funds have to comply with EC regulations on reference and discount rates. Simply put, guidelines have been developed as to the minimum cost of borrowing that can be charged so that it reflects market rates, i.e. is similar to what the private sector would offer and therefore does not breach state aid rules. To determine the actual rate, a new methodology has been drawn up by the EC that takes into account both the credit rating of the business and the collateral it will offer for the loan (table 2).

In this case, the credit rating is obtained from either from a credit agency or a national/government institution) and collateral should be understood as the level of collateral normally required by financial institutions as a guarantee for their loan i.e. the level of collaterals can be measured as the Loss Given Default (LGD), which is the expected loss in percentage of the debtor's exposure taking into account recoverable amounts from collateral and the bankruptcy assets. Therefore, ‘High’ collateralisation implies an LGD below or equal to 30 per cent; ‘Normal’ collateralisation an LGD between 31 per cent and 59 per cent and ‘Low’ collateralisation an LGD above or equal to 60 per cent.

Table 2. European Commission guidelines on loan margins.

Therefore, for an average SME with a satisfactory credit rating and normal collateral that is applying for a loan, the financial institution utilising European or state funding to support its loans programme must, to avoid a breach of state aid rules, charge a minimum of 2.2 per cent above the base rate. Currently, that would be 3.19 per cent (as the base rate is 0.99 per cent). Therefore, the interest rates to be offered can, depending on the creditworthiness and security offered by the business, range from 1.59 per cent to 10.99 per cent.

If EU member states apply the calculation method of these reference and discount rates in force at the moment of the grant of the loan and comply with the conditions set out in that communication, the interest rate does, in principle, not contain state aid. As a result, every publicly backed financial institution, to be compliant with state aid rules, applies the above principles to its debt lending and Finance Wales is no exception.

In a response to the review, Finance Wales stated that their

"State aid legal advice has consistently been based on the view that provided we are lending at a rate that is at least at the EC Reference Rate plus the appropriate risk margin, this is strong evidence that the loans do not contain State Aid. Clearly, the greater the margin over the minimum the stronger such evidence that the loans are at market rates. If we lent money below the minimum margins for the relevant Rating and Collateral indicative margins (most SMEs fall into the BB-CCC or lower categories with low collateral, therefore risk margins are typically 4-10 per cent), this argument of market rates would fall away and a potential state aid challenge become more likely.”

However, the evidence shows that Finance Wales is charging higher margins than that required by the European Commission to satisfy state aid regulations and that there are considerable differences between the cost of borrowing with regard to the reference rates proposed by the European Commission and the different rate categories offered by Finance Wales.

It would have been useful to be able to directly compare the fifteen different rates used by Finance Wales with their equivalent EC rate categories as shown in table 2. However, Finance Wales, despite providing the table below to the review, then withdrew permission to use it within the report. The rationale for this was that the information was commercially sensitive, the pricing guidelines are an internal document and, on their own, do not fully explains how risk is assessed on each investment. This was despite the fact that Finance Wales had already made public their three main categories of risk in the first report; that only thirteen investments in the current fund have been charged at less than eight per cent interest; and that, according to one of their senior executives, Finance Wales is not in competition with other funders as “most applicants to FW have been rejected by the usual sources for funding”.

Table 3. Finance Wales guidelines on loan margins

Nevertheless, the limited comparison of tables 2 and 3, using the published reference rates for three categories, shows that the difference between the EC reference rate proposed and the minimum cost of lending proposed by Finance Wales is as much as six per cent. It has been difficult to determine the scale of this overcharging, as Finance Wales does not keep detailed records of the collateral and credit rating of businesses on its internal IT system and, as a result, it has not been possible in the time available to determine how many businesses may have been paying above the suggested EC rates.

Therefore, the best proxy for this is to examine the individual rates of interest paid by each business according to the three main categories of risk supplied by Finance Wales. This estimates that if the EC reference rates had been adhered to accurately, up to 10 per cent of the current portfolio could have been paying interest rates as low as 1.99 per cent, and a further 50 per cent could have been paying interest rates as low as 4.99 per cent instead of 10 per cent. This would have been achieved without any breach of state aid rules. With regard to the interest rates for companies in bad financial difficulties with low collateral (which would be paying a minimum of 10.99 per cent), the EC recommended rate for Finance Wales is 12 per cent.

This suggests that Finance Wales could have lent at lower interest rates to Welsh SMEs without breaching state aid regulations if it had chosen to do so. In addition, there are also other costs that it charges to Welsh business on top of interest rates as part of the loan process. For example, average monitoring fees are 0.54 per cent, average arrangement fees are 1.8 per cent on current funds. In addition, Finance Wales also charges legal fees.

In responding to this study, Finance Wales stated that it regularly reviews its interest rates and benchmarks against various market indicators including LIBOR, Bank of England guidance on future rates and general competitor rates. Yet, whilst other state backed funds have kept their interest rates relatively low (e.g. Finnvera’s normal cost of borrowing to Finnish SMEs is in the range of 1.5 per cent to 4 per cent), there have been no substantial reductions in the cost of borrowing from Finance Wales even though the EC base rates have fallen since 2008.

As table 4 shows, whilst effective interest rates in the EC have declined during the last five years, Finance Wales pricing guidelines have stayed static until January 2013 when they actually were increased for ‘safer’ businesses but decreased for those businesses that can be considered as high risk. With Finance Wales being wholly owned by the Welsh Government, the decision to increase rather than decrease the cost of borrowing to Welsh businesses does not resonate with the current administration’s pledge to “ensure the maximum effectiveness and flexibility of all those Assembly Government departments and other organisations providing support for businesses, especially in these economically uncertain times”.

Table 4: Finance Wales guidelines on interest rates relative to EU guidelines.

The submission from the FSB noted that its members frequently came into contact with Finance Wales, believing it to be an organisation designed to support SMEs with investment but are then disappointed to find very restrictive and expensive lending conditions. One respondent noted: “My surprise to see that the offer on the table is more expensive in interest rates compared to the existing [High street bank] overdraft in place, the personal securities required are the same if not more stringent as from the bank, and on top Finance Wales is asking for 1.5 per cent lending fee, 0.5 per cent monitoring fee and a £275 security fee for the guarantee. This is a more commercial proposal based on stripping from any SME as much money as possible and in direct competition with the commercial banks and not offering small business any benefits at all.”

Therefore, many SMEs in Wales may find it difficult to understand why Finance Wales has not taken the opportunity to reduce its interest rates on loans, especially as there seems to be sufficient flexibility within the EC reference rate guidelines to do so.

Finance Wales’s strategy

As to all intents and purposes the sole shareholder, Welsh Government will need to determine the future strategic direction of Finance Wales and, more importantly, the role it should play in the future financial landscape for Welsh business alongside other providers. Given the evidence submitted by Finance Wales to this review, it can be argued that during the last few years, Finance Wales has predominantly focused on developing itself as an investment fund rather than as an economic development tool for the Welsh Government.

When Finance Wales was first established in 2001, its mission was to “assist Welsh businesses to realise their true potential for innovation, growth and economic impact in the region”. In addition, its key objectives were to:

• Increase the indigenous base of SMEs in Wales;

• Encourage diversification and development of new markets and products;

• Enhance capacity for Wales to grasp new competitive opportunities;

• Improve the growth rates of businesses accessing finance and

• Create new jobs.

So what was the logic behind this change in direction from the original focus on Wales and Welsh SMEs? According to Finance Wales, the organisation adopted a self-funding strategy in 2009 which had two main components - cost savings and efficiencies - and the pursuit of profitable fund management contracts which would both cover the cost of managing the funds and contribute to central costs (finance, IT, marketing), thereby reducing reliance on Welsh Government core funding.

Options were also considered in 2009 to “spin out” Finance Wales as a solution to a potential funding shortfall in the Welsh Government capital budgets of around £90 million. This followed discussions between Welsh Government and HM Treasury in late 2008 in which it was verbally agreed that Finance Wales’ borrowings from both Barclays and the European Investment Bank (EIB) of £95 million would not count against these budgets. Following a change of UK Government policy in 2008, these borrowings were then considered “on balance sheet” and Finance Wales was asked to consider ways in which it could to take its borrowings off balance sheet, which included becoming an independent commercial body.

During the two years it took to resolve the matter, the evidence suggests that Finance Wales therefore became more focused on developing itself as an independent fund with its role as an arm of the Welsh Government becoming a secondary issue. This is not only reflected in its lending policy, which is more similar to that of a private investment fund than an economic development body, but also its decision to move outside of Wales to manage funds in the North East and North West of England . This would enable it to earn management fees to move towards a self-funding position that would be necessary if the organisation was located outside of the public sector. This issue was resolved in 2010 when it was concluded that it was not financially or logistically viable to spin out Finance Wales and it would remain as part of the Welsh Government.

During the two years it took to resolve the matter, the evidence suggests that Finance Wales therefore became more focused on developing itself as an independent fund with its role as an arm of the Welsh Government becoming a secondary issue. This is not only reflected in its lending policy, which is more similar to that of a private investment fund than an economic development body, but also its decision to move outside of Wales to manage funds in the North East and North West of England . This would enable it to earn management fees to move towards a self-funding position that would be necessary if the organisation was located outside of the public sector. This issue was resolved in 2010 when it was concluded that it was not financially or logistically viable to spin out Finance Wales and it would remain as part of the Welsh Government.

Despite this decision, the evidence suggests that it is only recently that Finance Wales has begun to change its focus towards its economic development role. For example, in its 2010-11 annual review, its mission statement pronounced that it wanted “to become the UK’s leading SME Investment Company”. This was further emphasised by its decision to undertake the management of other funds outside of Wales - a direction that many respondents have questioned - and to compete directly with other financial institutions for new business.

With the appointment of a new Minister responsible for business and the economy in June 2011, a different direction was set out for the relationship between the Welsh Government and Finance Wales. In a letter to the Chairman of Finance Wales on September 20th 2011, the Minister stated that she wanted to see a “clearer alignment between the activities of Finance Wales and the priorities of the Welsh Government”. This included the appointment of a new independent board member to look after the Welsh Government’s interests.

It could be argued that this change in direction has been partly reflected in the new mission statement of Finance Wales, which is “to maintain our position as the UK’s leading SME fund manager, delivering commercial investments from public and private funds to support and encourage SME growth and create sustainable businesses in Wales, fully aligned with Welsh Government policies”. However, this wording still suggests a reluctance to move away from a primary focus as a private fund manager towards a greater role in supporting SMEs in Wales. That role, as will be discussed later, may include moving towards more affordable lending to businesses rather than focusing on generating surpluses in its funds, as a normal fund manager would do.

There is also a question regarding Finance Wales’ wider role in supporting SMEs in Wales. According to its own data, 915 business plans have been received from Welsh SMEs since 1st April 2012 of which 317 were declined (a rejection rate of 34 per cent) with the main recorded reason being the underlying viability of the business plan. The evidence to the review suggests that any rejected firms were only then introduced to the wider business support community on an ad hoc basis (although Finance Wales has now stated that it has recently introduced a more formal relationship with Business Wales to ensure reciprocity of introductions and more joined up support for mutual clients).

Therefore, the evidence submitted to this review indicates that there continues to be a reticence within Finance Wales to accept that it could have reduced the cost of borrowing to SMEs across Wales. More relevantly, it should have focused its efforts on developing the Welsh economy as its key mission and not only as a consequence of the management of its funds. If it is to retain the confidence of Welsh business community then it needs to address these issues.

Four weeks prior to the publication of this review, Finance Wales announced that it was planning to reduce interest rates for borrowings from the JEREMIE Fund, the SME Loan Fund and the Micro-business Loans Fund within the seven Welsh Enterprise Zones. This was a welcome development in that it demonstrated that, contrary to earlier claims during the first stage of this review, interest rates could be reduced by Finance Wales to support SMEs.

It also showed that Finance Wales could use the financial instruments at its disposal to reflect the economic development policies of the Welsh Government. Despite this, serious questions remain as to why Finance Wales had not previously considered utilising lower interest rates as an effective economic policy tool prior to this announcement and during a period of sustained economic crisis and reduced lending from the banking sector.

Exemptions for state aid regulations

In developing a policy of interest rate reductions for enterprise zones, Finance Wales has made the case that this decision does not breach state aid. Further research into the state aid issue raises questions as to why Finance Wales has previously not pursued greater flexibility through utilising mechanisms that would minimise the impact of state aid regulations on its ability to offer lower costs of borrowing to SMEs across other parts of Wales. However, the prohibition of state aid is not absolute and current state aid rules do allow public authorities, under certain conditions, to assist SMEs.

General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER)

By using GBER, loans financed under Structural Funds programmes can be rendered compliant by ensuring that the interest rates payable respect the grant equivalent thresholds, taking account of the relevant reference rates discussed earlier.

Advice received from the Welsh Government suggests that “GBER can be used for transparent forms of aid including loans. The calculation must take account of the reference rate at the time the loan is made. The aid element is the interest forgone by the public authority. For example if an interest free loan was made for a capital investment project, then the aid element would be the interest not collected by the public authority. You would of course need to ensure that all other terms and conditions are met e.g. the ‘free interest’ does not exceed the aid intensity when the eligible costs are taken into account, the company is not in an excluded sector etc.” Independent expert advice has confirmed this position.

Various policy papers (including these from the University of Strathclyde and the College of Europe) have also discussed how GBER can be used to minimise the impact of state aid regulations. The principles within these documents suggest that GBER could have been used to subsidise the interest rates on loans to SMEs within the two thirds of Wales classified as qualifying for the highest level of aid and been a significant policy tool for Welsh Government.

For example, with the maximum intervention rates for capital investment and employment for a small business operating within West Wales and the Valleys set at 50 per cent, interest rates could have been discounted by Finance Wales without breaching state aid regulations. Even within the non-assisted areas within East Wales, aid of up to 20 per cent on investment could have been provided in the form of cheaper loans for small firms.

De Minimis

It has also been suggested that the cost of borrowing could have been reduced for a high number of small firms through the use of de minimis aid. This describes small amounts of state aid that does not require formal approval i.e. the European Commission considers that public funding which complies with the de minimis regulation has a negligible impact on trade and competition and does not require notification and approval. The total de minimis aid which can be given to a single recipient is €200,000 over a three year fiscal period. This can be granted for most purposes and is not project-related.

Indeed, when it was first established in 2001, Finance Wales operated an interest rate rebate scheme and management support services under the de minimis rules. The de minimis rule is particularly important in terms of the financing of new businesses and micro-businesses, which are usually judged to have the highest risk profile because of limited collateral and credit ratings and therefore attract the highest level of reference rate. If the economic development aim of a government was to promote start-ups and micro-businesses, then a lower interest rate could be charged under the de minimis rules if a business did not breach the €200,000 limit on such aid within three years.

For example, the Start Up Loans programme established by the UK Government to encourage more young people to set up their own firms provides funding to start-ups and therefore should, according to the reference rates, be charged at the highest minimum level. With an average loan of £4,500, the de minimis rule is being used by BIS to lend money at a nominal fixed rate of 6.2 per cent instead of 10.99 per cent. Commercially, such a low interest rate would not normally be approved and there have been estimates that up to two fifths of the loans are unlikely to be repaid. However, this is justified as being a government policy decision to financially support young entrepreneurs in a time of economic difficulty rather than a commercial decision taken by a private organisation. For such a low amount, even lower rates can be charged without any risk of breaching state aid regulations.

Contrast this with the development of the new Micro-business Loan Fund in Wales that is a direct response to the recommendations of the Micro-business Task and Finish Group. Its final report, published in January 2012, identified that access to finance is a key barrier to growth for this size of firm and recommended that the Welsh Government should facilitate accessible finance of between £1,000 and £20,000 that is simple to access and reflects the level of investment required. As a result, the Welsh Government has provided funding of £6 million for a new loan fund that was launched earlier this year. As of the end of September 2013, this fund had invested in sixty-one micro-businesses with an average loan of £15,000 at an average interest rate of 11.2 per cent.

Whilst this rate of borrowing may be commercially sound, there is a question whether the approach taken by Finance Wales is one that reflects the economic development imperatives of the Welsh Government and the conclusions of the Micro-Business Task and Finish Group that “viable micro-businesses need viably-priced debt finance”. With the evidence from this review demonstrating that the lending to small firms continues to be stagnant, the cost of lending to micro-businesses by Finance Wales seems excessively high, especially compared to the Start-Up Loan programme currently operating in Wales and other micro-financing initiatives in other European counties (for example, Microfinance Ireland offers a fixed rate of 8.8 per cent to those micro-businesses being supported under its remit and Deutsches Mikrofinanz Institut in Germany, 8.9 per cent).

Therefore, it can only be concluded that that there have been no state aid impediment to Finance Wales offering cheaper loans to the vast majority of micro-businesses under de minimis regulations. Similar reductions could have been imposed across the £40 million Wales SME Loan Fund although Finance Wales has decided to apply the same rationale on borrowing to this fund. In fact, according to Finance Wales, no discussion has been undertaken with the Welsh Government over the cost of borrowing to be applied to the SME Loan Fund.

It also showed that Finance Wales could use the financial instruments at its disposal to reflect the economic development policies of the Welsh Government. Despite this, serious questions remain as to why Finance Wales had not previously considered utilising lower interest rates as an effective economic policy tool prior to this announcement and during a period of sustained economic crisis and reduced lending from the banking sector.

Exemptions for state aid regulations

In developing a policy of interest rate reductions for enterprise zones, Finance Wales has made the case that this decision does not breach state aid. Further research into the state aid issue raises questions as to why Finance Wales has previously not pursued greater flexibility through utilising mechanisms that would minimise the impact of state aid regulations on its ability to offer lower costs of borrowing to SMEs across other parts of Wales. However, the prohibition of state aid is not absolute and current state aid rules do allow public authorities, under certain conditions, to assist SMEs.

General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER)

By using GBER, loans financed under Structural Funds programmes can be rendered compliant by ensuring that the interest rates payable respect the grant equivalent thresholds, taking account of the relevant reference rates discussed earlier.

Advice received from the Welsh Government suggests that “GBER can be used for transparent forms of aid including loans. The calculation must take account of the reference rate at the time the loan is made. The aid element is the interest forgone by the public authority. For example if an interest free loan was made for a capital investment project, then the aid element would be the interest not collected by the public authority. You would of course need to ensure that all other terms and conditions are met e.g. the ‘free interest’ does not exceed the aid intensity when the eligible costs are taken into account, the company is not in an excluded sector etc.” Independent expert advice has confirmed this position.

Various policy papers (including these from the University of Strathclyde and the College of Europe) have also discussed how GBER can be used to minimise the impact of state aid regulations. The principles within these documents suggest that GBER could have been used to subsidise the interest rates on loans to SMEs within the two thirds of Wales classified as qualifying for the highest level of aid and been a significant policy tool for Welsh Government.

For example, with the maximum intervention rates for capital investment and employment for a small business operating within West Wales and the Valleys set at 50 per cent, interest rates could have been discounted by Finance Wales without breaching state aid regulations. Even within the non-assisted areas within East Wales, aid of up to 20 per cent on investment could have been provided in the form of cheaper loans for small firms.

De Minimis

It has also been suggested that the cost of borrowing could have been reduced for a high number of small firms through the use of de minimis aid. This describes small amounts of state aid that does not require formal approval i.e. the European Commission considers that public funding which complies with the de minimis regulation has a negligible impact on trade and competition and does not require notification and approval. The total de minimis aid which can be given to a single recipient is €200,000 over a three year fiscal period. This can be granted for most purposes and is not project-related.

Indeed, when it was first established in 2001, Finance Wales operated an interest rate rebate scheme and management support services under the de minimis rules. The de minimis rule is particularly important in terms of the financing of new businesses and micro-businesses, which are usually judged to have the highest risk profile because of limited collateral and credit ratings and therefore attract the highest level of reference rate. If the economic development aim of a government was to promote start-ups and micro-businesses, then a lower interest rate could be charged under the de minimis rules if a business did not breach the €200,000 limit on such aid within three years.

For example, the Start Up Loans programme established by the UK Government to encourage more young people to set up their own firms provides funding to start-ups and therefore should, according to the reference rates, be charged at the highest minimum level. With an average loan of £4,500, the de minimis rule is being used by BIS to lend money at a nominal fixed rate of 6.2 per cent instead of 10.99 per cent. Commercially, such a low interest rate would not normally be approved and there have been estimates that up to two fifths of the loans are unlikely to be repaid. However, this is justified as being a government policy decision to financially support young entrepreneurs in a time of economic difficulty rather than a commercial decision taken by a private organisation. For such a low amount, even lower rates can be charged without any risk of breaching state aid regulations.

Contrast this with the development of the new Micro-business Loan Fund in Wales that is a direct response to the recommendations of the Micro-business Task and Finish Group. Its final report, published in January 2012, identified that access to finance is a key barrier to growth for this size of firm and recommended that the Welsh Government should facilitate accessible finance of between £1,000 and £20,000 that is simple to access and reflects the level of investment required. As a result, the Welsh Government has provided funding of £6 million for a new loan fund that was launched earlier this year. As of the end of September 2013, this fund had invested in sixty-one micro-businesses with an average loan of £15,000 at an average interest rate of 11.2 per cent.

Whilst this rate of borrowing may be commercially sound, there is a question whether the approach taken by Finance Wales is one that reflects the economic development imperatives of the Welsh Government and the conclusions of the Micro-Business Task and Finish Group that “viable micro-businesses need viably-priced debt finance”. With the evidence from this review demonstrating that the lending to small firms continues to be stagnant, the cost of lending to micro-businesses by Finance Wales seems excessively high, especially compared to the Start-Up Loan programme currently operating in Wales and other micro-financing initiatives in other European counties (for example, Microfinance Ireland offers a fixed rate of 8.8 per cent to those micro-businesses being supported under its remit and Deutsches Mikrofinanz Institut in Germany, 8.9 per cent).

Therefore, it can only be concluded that that there have been no state aid impediment to Finance Wales offering cheaper loans to the vast majority of micro-businesses under de minimis regulations. Similar reductions could have been imposed across the £40 million Wales SME Loan Fund although Finance Wales has decided to apply the same rationale on borrowing to this fund. In fact, according to Finance Wales, no discussion has been undertaken with the Welsh Government over the cost of borrowing to be applied to the SME Loan Fund.

Summary

Following a request from the Minister, this section has undertaken a detailed review of Finance Wales and its approach to debt funding of SMEs. It has concluded, as many interviewees pointed out during the review, that Finance Wales was offering higher rates of interest on borrowing to SMEs within Wales. There may be sound commercial reasons as to why this is the case and arguments have been made that if it had been operating essentially as a commercial fund manager, albeit one owned by the Welsh Government, then the rationale for self-sufficiency as the key part of its corporate strategy explained a number of issues that have arisen in this report. There also remains the question why it has not utilised the full range of financial instruments available to it through both de minimis and GBER, especially for the convergence area of Wales that qualifies for the highest level of structural funding intervention.

Since the JEREMIE Fund was launched in 2009, the indication is it has operated a universal pricing tariff for JEREMIE-backed loan facilities irrespective of the geographical location of the borrowing entity. A similar approach has subsequently been adopted with the SME Loan Fund and the Micro-business Loan Fund. On the face of it, this appears to be an unusual approach given the existence of ‘match-funding’ in the form of ERDF and the higher intervention rates that are available in the poorest parts of Wales. Given the availability of such a geographically defined financial mechanism, one might therefore expect its operation would have been reflected in a territorially differentiated pricing structure. It has not, although this can be corrected within those financial instruments that will be developed for the next round of European Structural Funding.

That this situation has occurred is unfortunate since it suggests firms have faced a situation where the cost of capital provided by Finance Wales is greater than might otherwise have been the case. Whilst Finance Wales may have provided the finance needed at a time when the banks were not lending, it is reasonable to speculate that this policy may have discouraged viable businesses from applying for financial support and affected the financial management of those in receipt of funding during an economically challenging period. It is equally unfortunate that they have been allowed to persist and, inevitably, it raises questions about the degree and intensity of oversight that Finance Wales was subject to both internally and externally at the time of the launch of the JEREMIE Fund.

As the first report noted, it is still unclear as to whether Finance Wales is essentially operating as a commercially oriented fund manager in all but name. Whilst there have been welcome developments such as the appointment of new board members to drive forward the Welsh Government’s interests and the recent enterprise zone reductions, this has to be tempered with evidence of a reluctance by Finance Wales to fully embrace its role in supporting SMEs and economic development in Wales and its apparent confusion over its commercial ambitions with its development responsibilities. It has constantly used breach of state aid as its defence for its high interest rates and yet expert opinion in this report demonstrates that it could have lowered the cost of borrowing if it had so wished.

And despite the clear remit given to it by the current EST Minister, the most worrying aspect is that there is little indication of any change, as the following statement on the future of the organisation makes clear in its latest annual review: “The Finance Wales Group is a leading UK SME fund manager and we aim to be a sustainable long-term investment company. We raise our funds from a range of commercial and public sources and we need to ensure we achieve effective returns when we invest these funds.”

And despite the clear remit given to it by the current EST Minister, the most worrying aspect is that there is little indication of any change, as the following statement on the future of the organisation makes clear in its latest annual review: “The Finance Wales Group is a leading UK SME fund manager and we aim to be a sustainable long-term investment company. We raise our funds from a range of commercial and public sources and we need to ensure we achieve effective returns when we invest these funds.”

Therefore, if the role of Finance Wales is to support economic development and the SME sector in Wales, the evidence suggests that it is currently not fit for purpose in achieving this aim. As a result, the EST Minister may have a view as to how this role could change to achieve this aim, including bringing Finance Wales directly into the Welsh Government to fulfil the economic development role it has not prioritised in recent times. The next section may help to provide guidance on the strategy and structure need to ensure that Welsh SMEs get the best support possible to help develop the economy of Wales.